MRI is a fantastic imaging modality that has revolutionized radiology and imaging techniques over the last 20 years. With the advent of better software and more powerful 3T (Tesla) magnets, the image quality and diagnostic information obtained from modern MRI is staggering. MRI will enable pick up of pathology and normal anatomical variants in bone, articular cartilage (joint surfaces) and soft tissues (ligaments, tendons, menisci, labrum, tendon, muscle and adipose). These images are subject to human (radiologist, surgeon, physician, allied health professional) interpretation and as a result, inter-observer variation in the findings is common (in other words what may be seen as pathology by one observer may be interpreted as being normal when viewed by another). Being a highly sensitive test, pathological and variant conditions of the tissues are frequently seen. The big question is – Are all MRI findings reported relevant to the case at hand?

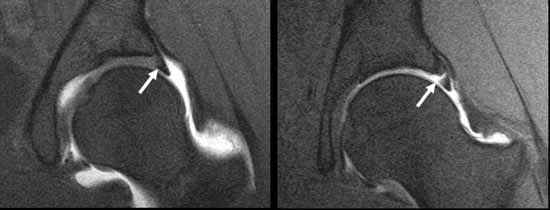

Figure 1. MRI scan of a normal acetabular labrum (left) and a torn labrum (right).

The short answer is no. Some findings on MRI are often incidental with no bearing on the cause of pain or other malady in a particular patient. The best person to determine this is your examining/treating doctor who has taken a thorough history, undertaken an appropriate examination and has ordered the MRI scan with particular questions in mind – namely to find evidence to support or discount a particular diagnosis. This doctor is then in the best position to interpret the MRI scan result for the patient. It is very common nowadays for patients to be referred on the basis of an MRI report alone. It is also fairly common for patients to read the MRI report, often seizing on various findings /key phrases and undertaking their own research on the conditions identified via Dr Google. Don’t get me wrong, sometimes this can be very helpful and lead to meaningful dialogue, but equally this can also at times be very misleading. Probably the most difficult consultation that a surgeon undertakes is a deconstruction of what is seemingly a “black and white” case in the mind of the patient based on an irrelevant MRI finding.

There have now been a number of MRI studies undertaken on asymptomatic individuals (with no symptoms whatsoever) looking for hip pathology, namely acetabular labral (hip cartilage) tears. The incidence of hip labral tear in children ranges from 2 to 10%, in young adults (medical students aged 18 to 25 yrs) it is up to 45% and in a population ranging up to 55years, the incidence is around 80%. All these so-called tears are in “asymptomatic” subjects who have no hip pain or symptoms. A number of these tears are probably interpretation “errors” due to tissue degeneration, vascular markings and labral sulci (recesses at the base of the labrum, which are a normal variant in the population) which will create a difference from the appearance of a normal labrum on MRI scan, but are not necessarily pathological.

Many patients with “hip” pain will have an MRI which indicates a labral tear. If their pain site /characteristics and examination findings are consistent with a labral tear, then and only then would a definitve diagnosis be made. Sometimes the pain location and examination findings are not consistent with a diagnosis of a hip labral tear at all, despite the MRI findings. This is where interpretation of all the facts is important to avoid unnecessary treatment / surgery. Some cases are borderline and sometimes other investigations/procedures (such as diagnostic injections of local anaesthetic) are required to establish a proper diagnosis.

Surgery undertaken without a proper diagnosis (exploratory) frequently results in poor outcomes for all concerned. Surgery undertaken with a firm diagnosis (on the basis of a consistent history, examination and investigation/MRI findings) and a well thought out plan of action has a far greater chance of a successful outcome.

Research Studies undertaken in this area include:

The prevalence of acetabular labral tears and associated pathology in a young asymptomatic population. Lee et al. Bone Joint J 2015;97-B:623-7. Link: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25922455

Identification of acetabular labral pathological changes in asymptomatic volunteers using optimized, noncontrast 1.5-T magnetic resonance imaging. Schmitz et al. Am J Sports Med. 2012 Jun;40(6): 1337-41. Link: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22422932

Prevalence of abnormal hip findings in asymptomatic participants: a prospective, blinded study. Register et al. Am J Sports Med. 2012 Dec;40(12): 2720-4. Link: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23104610