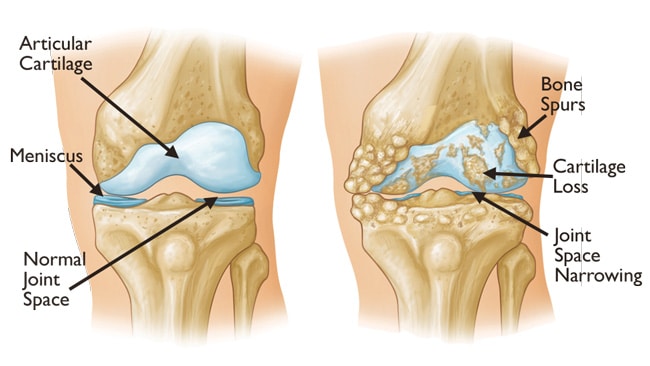

Knee osteoarthritis, like all forms of arthritis, is due to a loss of the cushioning joint surface tissue (articular cartilage) that covers the ends of the bones of the joint – the femur (thigh bone) above, the tibia (shin bone) below and the patella (kneecap) in front. This is a progressive condition and the natural history is one of slow deterioration – as the articular cartilage loss increases, so usually do the symptoms. When the articular cartilage layers are worn away completely, the joint articulates with “bone on bone” surfaces – this is usually very painful (as the bone has lots of nerve endings) and constitutes an advanced osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis differs from inflammatory arthritis in that the articular cartilage loss is due to “wear and tear” (a degenerative process – osteoarthritis is also known as degenerative arthritis) rather than due to an inflammatory process.

Figure 1. Normal knee (left) and Arthritic knee (right) with articular cartilage damage.

When thinking of the knee we divide it up into 3 compartments for the purposes of arthritis description – medial compartment (that part of the joint between the femur and tibia on the inside of the knee), the lateral compartment (between the femur and tibia on the outside of the knee) and the patellofemoral compartment (between the kneecap and the groove on the front of the femur). Arthritis can involve all three compartments (tricompartmental arthritis) or any combination of two or even a single compartment. It is common for the arthritis to have different levels of severity in different compartments at the same time. A common pattern of knee osteoarthritis is severe “bone on bone” disease in the medial compartment , moderate to severe disease in the patellofemoral compartment and mild or no involvement of the lateral compartment.

In most cases knee osteoarthritis is idiopathic (primary knee OA) – this means that there is no identifiable reason as to why it arises. Clearly as we get older there tends to be more natural wear of the joint surfaces (similar to the tread on a car tyre) but some knees never become arthritic despite advanced age. Presumably this has to do with the durability of the articular cartilage, which is probably genetically predetermined. Interestingly knee osteoarthritis can run in families. Similar to the car tyre analogy, lots of activity (driving) may predispose some individuals to more joint surface wear. It has been established for some time now that obesity is a major risk factor for the development of lower limb joint arthritis – there are both excessive load and chemical theories for this.

In some cases there are clearly identifiable reasons why knee osteoarthritis has occurred (secondary knee OA). The car tyre analogy here is that tread wear is more significant when the wheel balancing is poor. Predisposing conditions include alignment abnormalities of the knee and the patella. A bowed leg or varus alignment places significant stress on the inside of the knee and leads to wear of the medial compartment. A knock knee or valgus alignment does the opposite with excessive load and wear occurring on the outside of the knee or lateral compartment arthritis. Alignment abnormalities of the kneecap predispose to maltracking of the kneecap, which runs up and down a groove on the front of the femur (the trochlear groove). This can lead to the development of arthritis purely under the kneecap and it’s groove – so called patellofemoral arthritis – sometimes in the absence of arthritis anywhere else in the knee. Injury or damage to internal knee structures such as cartilages and ligaments can in some individuals predispose to the development of arthritis. Anything that injures the joint surface directly (eg. a fracture of the tibial plateau) or indirectly, (a traumatic dislocation of the kneecap) can start the wear process. Conditions such as osteochondritis and osteonecrosis can lead to joint surface damage and secondary knee osteoarthritis.

Figure 2. Varus knee alignment with bow leg leading to medial compartment arthritis (left) and valgus knee alignment with knock knee deformity leading to lateral compartment arthritis (right).

The main symptom/complaint with knee osteoarthritis is pain. This can be localized to one or other part of the knee but can be generalized depending on the distribution/site of the arthritis in the joint. It is unusual for pain from knee arthritis to radiate up or down the leg but sometimes pain can be present at the back of the knee if a fluid collection known as a Bakers cyst is present. One must be suspicious of either sciatica or vascular disease when pain located primarily in the lower part of the leg below the knee. In most cases, the pain comes on gradually without an obvious injury or incident. At the start the pain may only occur with or after heavy physical exertion like running, but as the condition progresses the pain may be felt with normal day to day walking and when end stage is often felt at rest. Patients will often notice difficulty with bending tasks, squatting, kneeling and negotiating stairs when the kneecap is involved.

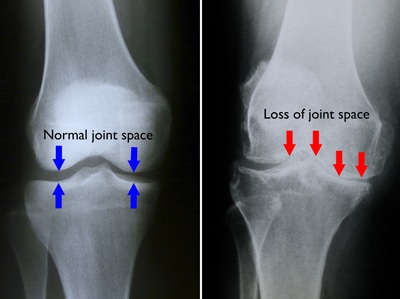

Knee osteoarthritis is often diagnosed on the basis of history and clinical examination. It is usually easily confirmed on plain xray, but sometimes more extensive investigations like MRI scan can be helpful particularly in the early stages of the condition.

Figure 3. Xray of a normal knee with preserved joint spaces (left) and arthritic knee with loss of medial joint space (right).

Knee osteoarthritis is a complex condition and there are no treatments that will reverse the joint surface wear changes once they have started to take place. The treatment or management of osteoarthritis of the knee needs to be tailored to each individual depending on the severity of the condition and how this is affecting the person afflicted. In the early phases of this condition when the symptoms are mild, conservative or non-operative treatment is usually recommended. Conservative management principles centre around education of the condition, activity and lifestyle modification, weight reduction, the use of physical aids and the careful use of medication for symptom reduction or relief. Specialised exercise programs can be helpful win patients with patellofemoral arthritis. There is a limited place for injectable treatments in knee arthritis. These measures are about making it easier to manage with the symptoms (usually pain and stiffness) on a “day to day” basis.

Operative management or surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee is really only indicated for end stage “bone on bone” joint surfaces. Surgery for early or middle stage disease in most cases does not significantly improve symptoms or function. Arthroscopic surgery is not generally helpful in an arthritic knee unless there are significant mechanical symptoms (locking or catching) and where a displaced meniscal tear or loose body is present. In patients with advanced but isolated single compartment arthritis, realignment procedures (osteotomy) or partial unicompartment knee replacement surgery (UKR) can be considered.

Total Knee Replacement (TKR) is generally the treatment of choice for advanced knee osteoarthritis where 2 or 3 compartments are involved for the patient with unmanageable pain and very significant impairment of function (ability to walk, bend and undertake simple activities of daily living). It should be noted that TKR is a compromise operation and will never provide the recipient with a completely normal knee. TKR is however generally very successful in providing significant pain relief and restoration of function in a significantly impaired individual with end stage disease.