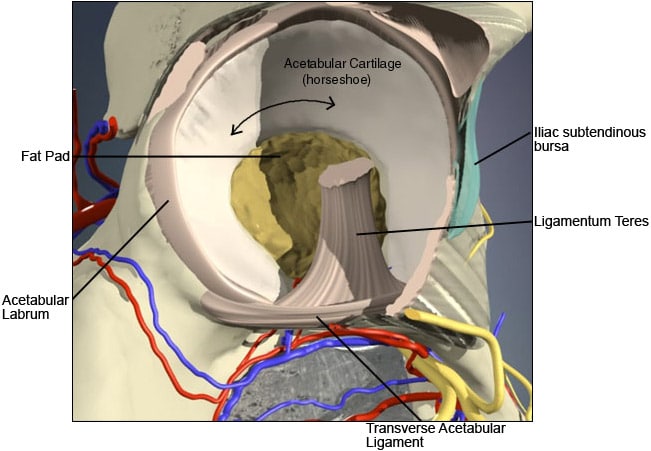

Labral tears are a common cause for hip pain. The acetabular labrum is a fibrocartilaginous structure that sits around the rim of the socket of the hip. It is triangular in cross-section. It is very similar tissue in structure to the glenoid labrum of the shoulder and the meniscus (“cartilage”) of the knee and is colloquially known as the “cartilage” of the hip.

Similar to the meniscus of the knee (which has been extensively studied), the labrum of the hip performs a number of important functions for the joint. It is almost certainly involved in some way in load transmission across the surfaces of the hip and assists with the flow of lubricating synovial fluid throughout the joint. The labrum acts as a “seal” and deepens the joint – important for stability and contains proprioceptive receptors that allow impulses to be sent to the brain regarding the position of the joint and its attached leg, which is important for balance, co-ordination and injury prevention.

The labrum of the hip (again similar to the knee meniscus) has only a limited capacity for repair when damaged. The base of the labrum where it is attached to the bone of the hip socket (the acetabulum) has a blood supply that comes directly from the bone itself. Injury or tears to the labrum in this vascular zone have some capacity for healing. Unfortunately the free edge of the labrum has a very limited or poor blood supply and damage to this portion of the labrum generally results in tears that have no significant capacity to heal by themselves. The site of damage of the labrum clearly has significant implications with regard to how they are treated.

Labral tears of the hip fall into 2 main categories.

The first of these is the “acute” tear – which generally occurs in younger individuals pursuing athletic activities. In this group, there is frequently a significant injury or incident involving forced rotation or hyperabduction (“doing the splits”) of the hip. There may be a noise or sensation of damage felt within the hip or groin followed by immediate onset of pain. A proportion of these types of labral injury involve the vascular zone.

The second is the “degenerative” tear – which tends to occur in individuals over the age of 35 years and usually without a preceding injury or incident. The internal structure of the labrum “dries out” as we age – losing elasticity and flexibility – and as a result it is prone to small surface splits or damage that with time and “normal” use can progress to a significant tear. Many of these tears are asymptomatic – they cause no problems at all, even though they can be seen on investigations like an MRI scan. We know that degenerative tears of the labrum become more frequent with age and that a high percentage of the population over 65 years of age have them. If a degenerative tear of the labrum creates an unstable segment or “flap” that can move around abnormally or get caught between the ball and the edge of the socket – it can create pain inside the hip.

Labral tears of the hip cause pain and this is classically felt deep over the anterolateral aspect of the groin in what is called the “C” sign – so described because of the classical hand position used when showing the position and distribution of the pain (see figure).

Figure 2. The “C” sign – a demonstration of the site/distribution of typical labral tear pain.

This pain location corresponds with most tears (around 90-95%) of the labrum being at the front (anterior) or top (superior) of the hip. Tears of the labrum at the back of the hip (posterior) are unusual but may cause pain felt deep in the buttock. Pain is felt with significant physical activity (running & sport), often with changing direction or certain rotational movements of the leg and often when the hip is repeatedly flexed particularly under load (squats, cycling in an aerodynamic position etc.) Tears can cause clicking with various movements of the hip. This kind of clicking is usually painful. Clicking in the hip however can be due to a number of different causes, most of which are innocent. If a labral tear is of sufficient size it can cause mechanical symptoms – catching, jamming, locking or a sensation that something goes in and out of place inside the joint.

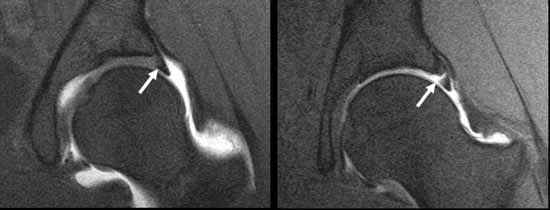

Plain xrays are a good first investigation in anyone with suspected hip pain/pathology, even though xrays are most frequently normal or may show some degenerative joint changes. The best investigation for diagnosing a labral tear is undoubtedly an MRI scan with or without intrarticular gadolinium (a contrast agent injected into the joint). In a lot of cases tears can be seen directly by the scan but sometimes only small fluid collections are seen on the external surface of the labrum – these collections are called paralabral cysts and are a strong indication that a labral tear is present. A labral sulcus – a groove or pit seen between the labrum and its attachment to the edge of the acetabulum (seen in about 35% of hips) is often mistakenly reported as a “tear” on MRI.

Figure 3. MRI scan of a normal labrum (left) and a labral tear (right).

It should be noted that labral tears can co-exist with other hip pathology – particularly hip impingement in younger individuals and osteoarthritis in older patients – and these other pathological entities need to be considered when investigating and mapping out a treatment plan.

Not all labral tears require treatment. Assymptomatic (non painful) tears identified on MRI scan and tears associated with significant osteoarthritis do not require any specific treatment. Symptomatic (painful) tears without mechanical symptoms can be managed in some individuals without surgery, by a combination of avoidance or modification of exacerbating activity (ie altering cycling position), physiotherapy techniques to correct muscle imbalances that are often present and the use of analgesic and anti-inflammatory medication for pain relief. Conservative treatment may be indicated initially in “acute” tears where there is some prospect of spontaneous healing. Surgery in the form of hip arthroscopy is indicated in patients with painful tears unresponsive to non-operative treatment or tears with clear mechanical symptoms. Arthroscopic treatment generally involves resection of the torn segment of the labrum and smoothing of the remaining labral surface but repair of the labrum can be undertaken in cases of detachment or vascular zone tears in an otherwise healthy labrum – this unfortunately is not a common situation. As a general rule “acute” tears in healthy labral tissue tend to respond best to surgical treatment, whereas the outcome in “degenerative” tears is more variable.

Figure 4. An arthroscopic view of a labral tear being trimmed.

Source: https://www.parkclinic.com.au/labral-tear-of-the-hip/