Hamstring tears are one of the commonest injuries in an athletic population. They account for the most weeks missed each year amongst AFL footballers. Most of these tears involve either the hamstring muscle belly or the distal musculotendinous junction. Proximal hamstring injury however is uncommon. In the overall hamstring injury spectrum, it accounts for less than 10% of all hamstring injuries.

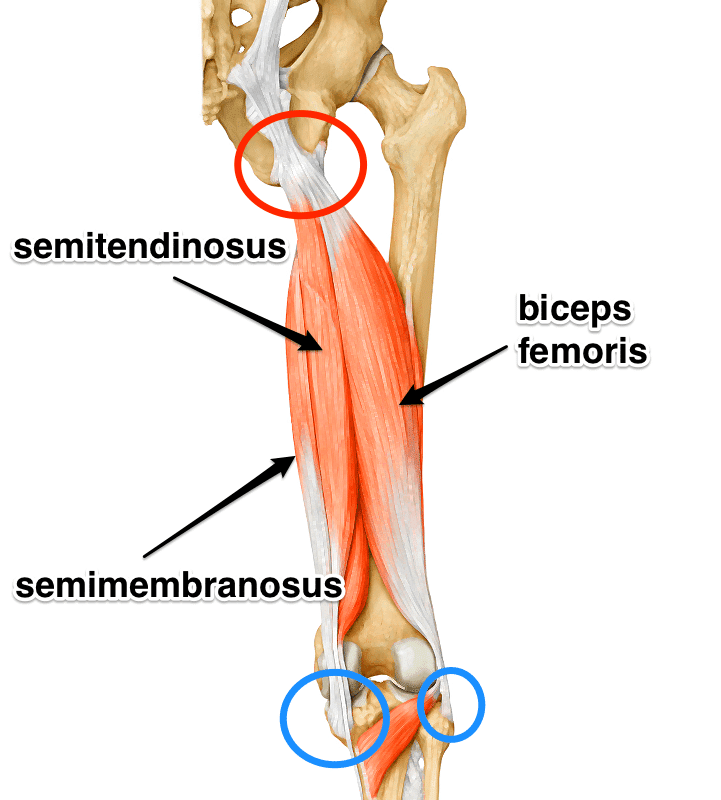

Anatomy

The hamstring comprises most of the muscle bulk of the back of the thigh. It is important for pushing off, jumping and landing and particularly for explosive activity like sprinting. The hamstring is made up of 3 muscles, each with a common proximal attachment via a large tendon to the ischial tuberosity of the pelvis (the large bone one sits on in the buttock). This proximal attachment provides a fixed point from which muscle contraction can affect a more distal action – the hamstring provides some extension of the hip but the main action is movement around the knee. It is the main muscle group responsible for knee flexion. The 3 muscles – biceps femoris, semitendinosus and semimebranosus form in the posterior thigh and attach distally around the knee via tendons to bony landmarks, crossing the joint as they do so. The biceps attaches laterally to the head of the fibula on the outside of the knee. SM & ST attach to the medial side of the upper tibia. The sciatic nerve runs very close to the proximal tendon attachment to the ischium and can be injured together with the hamstring.

Demography

Proximal hamstring injury occurs in 3 distinct populations. Firstly the adolescent who is not skeletally mature can avulse the hamstring origin with a fragment of bone from the ischium. The second group are young, skeletally mature, athletic individuals and the third group are older patients, often in their 50’s who may be sedentary or participate in recreational sports.

Mechanism of Injury

The proximal hamstring tendon either gets injured through progressive stretch or more commonly by powerful eccentric contraction when the hip is suddenly and forcefully flexed over an extended knee. In younger patients with normal proximal tendon this occurs with sprinting or hurdling but the classic group affected are waterskiiers who fall forward with an extended knee. This is generally a high energy injury. In the older population, proximal hamstring injuries occur with lower velocity trauma such as slipping on a wet surface or doing the “splits” inadvertently.

Type of Injury

Proximal hamstring injury can be complete tendon ruptures or incomplete/partial tears. In the adolescent the bone with tendon attached is often avulsed or fractured from the pelvis (ischium). In mature patients, the tendon usually avulses or tears off the bone of the ischium at its attachment point. Occasionally the tendon may tear in its midsubstance leaving a stump of tendon still attached to the bone. Often this type of injury is a partial tear.

Presentation of Proximal Hamstring Injury

Classically there is a traumatic incident and the patient/victim feels something “go” deep in the buttock. If the incident is observed often the victim will grab the buttock or upper thigh – the so called “clutch” sign of hamstring injury. They are generally not able to continue with activity and if on the ground may need assistance to get up and to walk. There is usually immediate pain and weight bearing on the affected leg is very difficult and so crutches are usually required. It is painful to sit on the affected buttock. Over the next 24-48 hours there is usually swelling and bruising that appears over the buttock area, which then extends down the back of the thigh and sometimes even into the lower leg. Occasionally there can be pins and needles in the foot or lower leg and rarely loss of movement in the foot can be seen with a foot drop. These injuries usually necessitate a visit to hospital initially or to a general practitioner or a physiotherapist, where a diagnosis can be made or at least suspected.

Figure 2. The “Clutch Sign” of hamstring injury.

Figure 3. Bruising of the buttock and posterior thigh seen in proximal hamstring injury.

Investigation

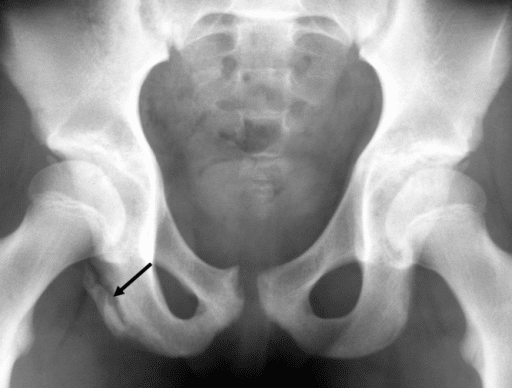

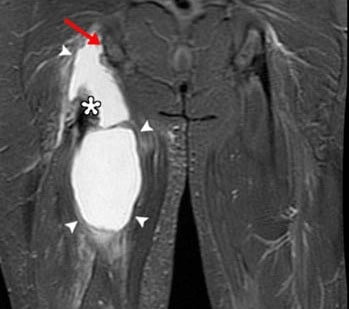

Xrays are important in younger patients to rule out an avulsion fracture of the ischial tuberosity. Ultrasound can be undertaken and will identify a haematoma (blood collection) in the buttock and upper thigh and can detect tendon tears but in my experience the accuracy of this test for determining the exact nature and type of injury is at best variable and at worst completely inaccurate. MRI scan is the investigation of choice and is highly accurate at determining the site of injury, whether the tear is partial or complete and importantly telling whether there has been any retraction of the tendon end into the thigh.

Figure 4. Avulsion fracture of the ischial tuberosity. This bone fragment has the proximal hamstring tendon attached to it.

Figure 5. MRI scan of a normal hamstring tendon (right) and a torn proximal hamstring tendon (left). Ischial tuberosity (red arrow), torn proximal hamstring tendon end (asterisk) and haematoma or blood collection (white area marked by arrows).

Treatment

Initial treatment in the first few days should be symptomatic – measures to reduce pain and swelling with icing, analgesia and the use of crutches to assist walking. As the pain starts to settle some gentle movement of the leg can be undertaken and the assistance of a physiotherapist at this point can be very helpful.

Once the diagnosis of a proximal hamstring injury is made, it is important to get a specialist opinion regarding treatment options. Conservative treatment with a rehab program may be appropriate in sedentary older patients or in those with partial tendon tears where a significant proportion of the tendon is still intact. Conservative treatment is generally also undertaken in most cases of bone avulsion fracture where the bone fragment is sitting close to the ischium (within a couple of centimetres – as these fractures heal quite rapidly even with some displacement). Operative repair of the tendon is generally recommended in younger, athletic patients or older victims who wish to continue with sports or active recreations, where there is a complete tendon tear.

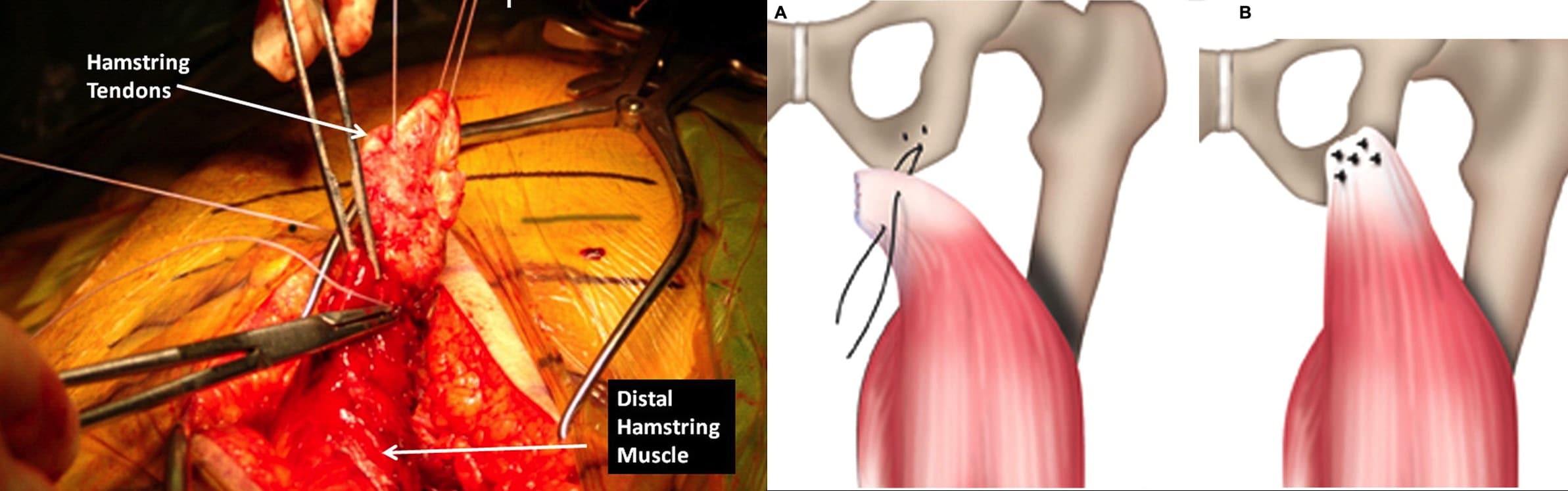

Surgical repair usually involves an overnight stay in hospital and the procedure itself is performed under a general anaesthetic. An incision is made in the buttock/upper thigh and the torn tendon end is identified, mobilized if it is retracted down into the thigh and then repaired back down onto the bone using bone anchors or transosseous (through bone) sutures. The sciatic nerve is protected during the surgery.

Figure 6. Surgical repair of the proximal hamstring tendon to the bone of the ischial tuberosity.

After surgery, painkillers are required and I personally like patients to rest lying on their back with a pillow under the knees – to allow the hamstring to be in a relaxed, not tight, position. I’m happy for patients to get about with crutches putting a small amount of weight on the ball of the foot maintain some flexion in the knee. At the post operative review at 2 weeks, stitches are removed and gentle and controlled hip and knee movement is begun with a physiotherapist and if comfortable crutches can be gradually weaned. At 6 weeks some resisted hamstring activity can be commenced and possibly a return to light running at 3-4 months. Return to competitive sports may be considered after 6 months. These timeframes are guidelines and may vary according to the injury and the individual.

Late Presentation

Sometimes patients who have had a proximal hamstring tear present late (3-12 months after injury) for an assessment and treatment. There are a few reasons for this. It can relate to the diagnosis not being made or the seriousness not being fully appreciated. Some people don’t seek medical or physio attention after this injury and push on. Unfortunately these patients often have continuing issues with pain and weakness or inability to pursue significant or sporting activity.

These patients are unfortunately a difficult group to treat satisfactorily. MRI scan of these patients often reveals a tendon that is encased in a mass of scar tissue often quite a distance away from its attachment to the ischium. The sciatic nerve is also often surrounded by scar. Surgery is these patients is fraught with difficulty. Firstly it is difficult to identify the tendon end and to mobilise it enough to allow proper reattachment. The main risk is of damage to the sciatic nerve in trying to free it from the surrounding scar and tendon tissue. Sciatic nerve damage in this circumstance can result in a far greater and permanent incapacity than persistent issues from the hamstring tendon itself. For these reasons, generally these patients are managed with a rehab program acknowledging that this may not resolve all issues nor necessarily allow a return to all activities.